Danielle Taylor, of Pennsylvania Great Outdoors, submitted the following article on Presidential Legends in the Pennsylvania Great Outdoors Region:

Danielle Taylor, of Pennsylvania Great Outdoors, submitted the following article on Presidential Legends in the Pennsylvania Great Outdoors Region:

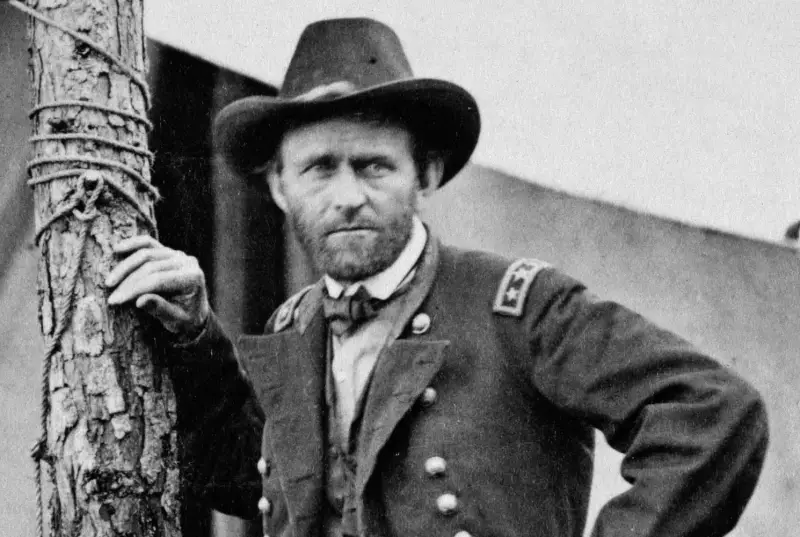

(PHOTO: President Ulysses Grant)

For Presidents’ Day in 2018, we shared some of the many “Presidential Connections to the Pennsylvania Great Outdoors Region,” and this year, we’ve dug up some more stories of presidential visits to and affiliations with this peaceful region, a world away from the constant chaos of Washington.

President Grant found a number of excellent fishing spots on his visits to Elk County. Photo: Jeff London.

President Ulysses Grant visited Elk County on three different occasions, and on his third trip in November 1883, he and his fellow traveling dignitaries visited a schoolhouse that’s now part of the Riverside Lodge in Wilcox. The schoolhouse was only three years old at the time of his visit, and anecdotal evidence passed down over the years suggests that President Grant spoke to the children at the school. An avid fisherman, he likely also dropped a line into the East Branch of the Clarion River that runs just a few yards away from the building. Elk County records verify that he fished between Johnsonburg and Wilcox at the Tambine Bridge, and he even got mock arrested for fishing without a license at Tambine — undoubtedly a publicity stunt.

On this visit, President Grant stayed at what was then called the Wilcox House and signed his name in the ledger on November 5, 1883. The Wilcox House owners changed their property’s name to the Grant House and kept the room where the president slept intact as it was during his visit until the building burned down more than 100 years after his stay.

Jefferson County has been graced with visits by Presidents Calvin Coolidge and Bill Clinton, but perhaps President William Howard Taft’s trip left the most interesting legacy.

According to Ken Burkett, executive director of the Jefferson County History Center, President Taft stayed at 100 Franklin Street in Brookville on December 19, 1918, and spoke to 1,300 people at the Methodist church in Brookville. He was also scheduled to speak to a teachers’ group in the area as well. When the county Republicans got word of his pending visit, they prepared a formal banquet at the Brookville YMCA and sold tickets for $3.50, and attendees arrived in top hats and white gloves preparing to meet the president. However, President Taft never showed. His speaking engagement for the teachers’ association was already scheduled for the same time as the banquet, so he went to that instead. The Jefferson County History Center still has a top hat that one of the attendees wore to the event.

Perhaps the most interesting president-related legend from Jefferson County, however, is the story of noted historian and author Kate Scott. Scott served as a nursemaid for the 105th Regiment of Pennsylvania Volunteers during the Civil War, and in an alleged sworn statement made in 1910, she made a shocking claim to Lincoln scholar Osburn Oldroyd about John Wilkes Booth, widely known as the assassin of President Abraham Lincoln.

In the statement, Scott writes that she met Booth at a military ball in Washington during the course of her nursing service, and he began to call on her and take her to a number of social functions. She did not feel she could capture his heart as she hoped, and she returned home to her family Brookville in June 1862. That fall, Booth came to visit while traveling to Meadville, Pennsylvania, (now Meadville) for business, and he continued to stop in to see Scott whenever he passed through the area. On one trip in February 1865, she traveled with him to Meadeville and then to Washington, and she alluded to circumstances with him that led to the birth of her daughter in December 1865.

In the meantime, an assassin shot and ultimately killed President Lincoln in April 1865, and Booth was quickly identified as the murderer. Two weeks later, reports came that he had been killed in Virginia. Scott wrote of her shock at Booth’s role in the president’s assassination but came to the conclusion that it must have been true, and she lamented the loss of his talents with his death. At this point, her statement veers from official history. That July, she wrote, she received a letter from Booth in his handwriting that asked her to retrieve an envelope from his business contact in Meadeville and have it ready for him at her family’s farm that September. She did so, fearing a hoax, but then wrote that he appeared as scheduled, minus his trademark mustache.

Did John Wilkes Booth, supposed assassin of President Abraham Lincoln, visit Brookville weeks after the federal government said he had been killed and leave behind a mistress and daughter? Decide for yourself!

According to this account, Booth spent a week at the farm with her and told her of his plans to travel to Canada, secure funds from his account with the Bank of England, and move to India. She begged him to take her along, and he said he would send for her later. However, it seems he never did so. Scott states that she received several letters from him after he had traveled to England and then India, and she notes his death in the early 1880s.

It’s easy to dismiss Scott’s claim and assume she wanted attention for a false connection, but she was a well-educated woman of the time who worked as a newspaper columnist, authored two books on Jefferson County history, and served a number of charitable causes and organizations, so she doesn’t seem the type to make such a volatile assertion without cause. Jefferson County History Center curator Carole Briggs spent years researching Scott’s life and connection with Booth, and she published “Kate M. Scott: Did She or Didn’t She?” outlining her findings. Briggs’ book, available for purchase at the Jefferson County History Center, makes strong arguments against Scott’s story, deducing that “Kate never gave this deposition to Osburn Oldroyd,” but readers and other researchers may come to different conclusions.

For more details on interesting history throughout the region, contact or visit the Jefferson County History Center, Clarion County Historical Society, Elk County Historical Society, Forest County History Center, and Cameron County Historical Society. Each offers exhibits, artifacts, and information that highlight the unique history of this region and the people who helped shape it.

Learn more and find other interesting places to visit in the Pennsylvania Great Outdoors region by going to VisitPAGO.com or call 814-849-5197.

Copyright © 2024 EYT Media Group, Inc. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of the contents of this service without the express written consent of EYT Media Group, Inc. is expressly prohibited.